It’s hot, I’m tired and I need to take a shit. Welcome to the Amazon…

The heat and fatigue are pretty self-explanatory. The shit, not so much. I was thinking something I ate after landing in Peru, until I flashed back to a foggy, jetlagged memory of guzzling water in a Lan Chile toilet 30,000 ft over El Salvador. Now, I’m pretty sure it’s Giardia. Oh well, what are you going to do?

No, literally, what am I going to do? It’s March 2016. We’re days up a tributary, deep in some of the world’s most remote jungle. We’re here to collect ticks, fleas and mosquitos. Well, Dr Ryan Jones, a microbiology Professor, and his student Nick Pinkham are; I’m here to collect images (and intestinal parasites, it seems).

We’ve collected hundreds already. It’s the last week of our month-long expedition, skimming across the Peruvian Amazon in a speedboat rented for us by National Geographic. Every morning our skipper pulls into another tiny village and we go ashore to ask stunned locals,

Puedo tomar las pulgas de su perro? Can I take the fleas from your dog?

Jones’ aim is to shed light on infectious-disease vectors in this part of the world. Specifically, are the microbes that live in the vectors affecting transmission of the infectious diseases themselves? His previous research suggests they probably are, now he and Pinkham are here to find out for sure.

It’s the perfect place for it really: hot, wet, remote and unvaccinated – everything a good infectious disease could want.

It’s the perfect place for it really: hot, wet, remote and unvaccinated – everything a good infectious disease could want.

‘I bet gringos come to collect fleas here all the time, right?’, Jones jokes with the locals.

They appreciate the irony. They’re facing the confronting reality of living with dangerous diseases on a daily basis, in places where the doctor visits once a year.

Malaria, Dengue, Yellow Fever, Chikungunya. The list goes on. Zika isn’t here yet, but it will be soon…

The kids run to meet the sound of our boat. Jones finds the ‘Heffe’, or boss kid, who splits the gang into twos and threes. They dive under houses and upturned canoes, returning with puppies and ‘perros simpatico’, nice dogs, who won’t mind having their fleas sampled by two gringos and their 30 helpers.

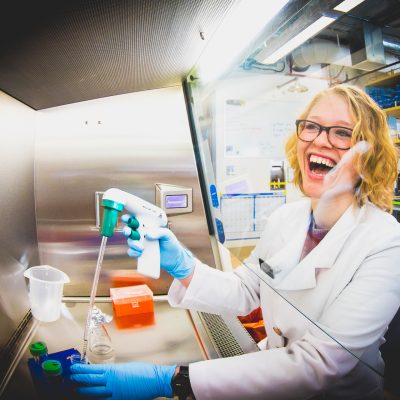

Pinkham does the dirty work. On all fours in the dirt, he gets the kids to hold the dogs still, while he combs through the fur in search of his Masters. Mostly, he’s successful. Fleas and ticks make their way into sample tubes. Later, he’ll use a fancy grinder to extract the DNA from them, and their bacteria.

To collect mosquitos, Jones and Pinkham use a different method. They stand waiting in the jungle at twilight, sweating and wise-cracking, until a mosquito lands on their partner – this typically leaves them time for one insult each, although Jones mostly pulls rank and gets two shots in first. Then, they use a flexible rubber hose to suck the killers into glass straws.

To collect mosquitos, Jones and Pinkham use a different method. They stand waiting in the jungle at twilight, sweating and wise-cracking, until a mosquito lands on their partner – this typically leaves them time for one insult each, although Jones mostly pulls rank and gets two shots in first. Then, they use a flexible rubber hose to suck the killers into glass straws.

Through it all, I fire away with my camera. Zoom in. Zoom out. Get low. Get high. Climb on a patio. Peer through a window. After 4 weeks, though, I’m starting to accept there’s a finite number of ways to shoot a grad student taking a flea off a dog. Instead, having covered the science, I turn my attention to the people.

The adults are very photogenic, with stoic frowns and smiles worn-in by lives of fishing and farming. The kids are great too. The ones that look 6 are actually 12, most of them are quiet and all of them are cheeky. They find great thrills in the process of having their picture taken, but aren’t really interested in the results.

The adults are very photogenic, with stoic frowns and smiles worn-in by lives of fishing and farming. The kids are great too. The ones that look 6 are actually 12, most of them are quiet and all of them are cheeky. They find great thrills in the process of having their picture taken, but aren’t really interested in the results.

I joke with them in my terrible Spanish,

Donde est su barba? Where’s your beard?

They laugh. I remind myself to be more like them.

Then I ask, gravely,

Donde est el bano? Where’s the bathroom?

—

Check out my gallery of images and a video I shot on National Geographic Expedition Raw.